New USMCSA Deal Protects Big Tech From Liabilities, Except Online Sex Trafficking

One of Silicon Valley’s concerns in the re-negotiation of NAFTA was in the area of free speech and content regulation, and the final draft turned out to be good news for Big Tech — mostly.

According to the new United States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement (USMCA), tech companies like Facebook and Google will not be liable or prosecutable for any content they host on their sites, even if that content is false or illegal. There is, however, one exception: the new agreement says the U.S., Mexico and Canada can enact “measures necessary to protect public morals” and hold tech companies liable for content that facilitates sex trafficking, child trafficking and prostitution.

The agreement mimics Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which several libertarian experts have praised for protecting tech companies from liabilities and lawsuits related to the content curated on their sites. The Electronic Frontier Foundation calls the CDA’s Section 230 the “most important law protecting internet speech.”

That protection ends when it comes to sex trafficking. The new USMCA specifically references the U.S.’ amendment to the Communications Act of 1934, passed earlier this year, the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act of 2017 (commonly referred to as FOSTA), which Silicon Valley lobbied against.

FOSTA was the result of an 18-month Senate investigation into Backpage.com, a website notorious for facilitating online sex trafficking and sexual exploitation of children. Thanks to FOSTA, tech companies can be held liable for knowingly running ads for sex trafficking and child sex.

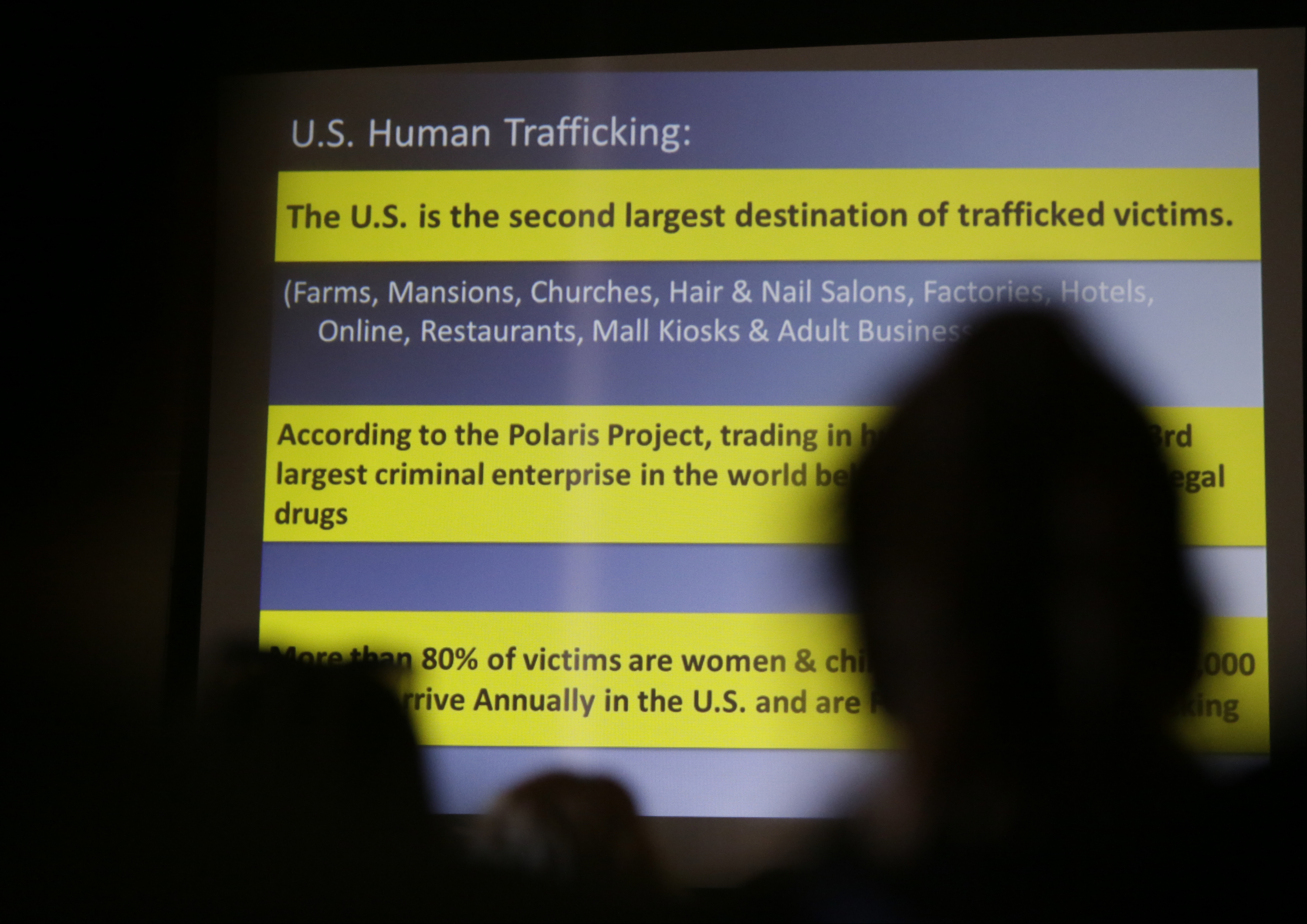

Lisa Thompson, vice president of research and education at the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, said neglecting to hold tech companies liable for this in the new NAFTA agreement would encourage cross-border sex trafficking, which has increased rapidly over the past 10 years, especially at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Simply copy-and-pasting Section 230 language into the new NAFTA agreement, she wrote in an op-ed for The Hill, would “be nothing short of a sex-trafficking apocalypse.”

Silicon Valley — including many tech publications and libertarian voices — decried FOSTA for restricting internet freedom, and Google lobbied earnestly against its passage. The tech industry also lobbied for the new NAFTA agreement to include Section 230 language without caveats. According to a Quartz report, internet and tech companies and associations spent $38 million on lobbying through August this year.

According to two lawyers in an analysis published by Bloomberg, “The safe harbor [of Section 230] has always been a double-edged sword. For platforms, the task of monitoring user content and responding to demands to remove defamatory or otherwise unlawful third-party content could easily become so onerous as to be infeasible. On the other hand, for parties aggrieved by unlawful postings, it can be immensely difficult to cause an unresponsive platform to remove even obviously wrongful — even demonstrably illegal — content or speech.”

In an August 2017 letter to congressional staffers, Google lobbyist Stewart Jeffries wrote that FOSTA “has the potential to seriously jeopardize the internet ecosystem” and “undercut[s] one of the foundational statutes for the Internet: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.”

During Google’s Q2 2018, Jeffries lobbied the United States Trade Representative (USTR) on behalf of Google on a number of issues related to the NAFTA (now USMCA) renegotiation, like “freedom of expression and free flow of information,” as well as lobbying Congress over “anti-human trafficking” and FOSTA.

Aware of the tech industry’s push, rescued victims of sex trafficking sent a letter to Congress in September asking for the “Section 230-like language” in the new NAFTA agreement to be modified to hold internet and tech companies liable for “knowingly facilitating” sex trafficking.

Beyond Borders ECPAT Canada, a national advocacy organization seeking to end exploitation of children, said Canadian representatives in the NAFTA renegotiation responded to concerns “that the agreement might include a blanket prohibition which would prevent Canada from imposing liability on internet providers for content. We are pleased to see that the agreement would allow Canada to hold internet providers liable for online sexual exploitation of children.”

Beyond Borders ECPAT Canada also applauded FOSTA earlier this year.

While the USMCA is still a huge win for Silicon Valley, the tech industry’s resistance to anti-sex trafficking efforts may only strengthen anti-Big Tech sentiments in Washington as scrutiny of some of the major players — like Google, Facebook and Twitter — intensifies.