The data are clear: Remote learning is a “disaster” for public school students. So why are so many New Hampshire public schools forcing students into it?

It’s a decision that has parents literally protesting in places like Nashua, and it flies in the face of both the available national research and the local New Hampshire numbers on COVID-19.

New Hampshire ranks as the fifth safest state for school reopenings in the nation, a recent analysis shows. And according to the New Hampshire Department of Health & Human Services (NH DHHS) Commissioner Lori Shibinette, New Hampshire students have an incredibly low positive test rate of less than 1 percent, a month after many schools have reopened.

Yet, despite this impressive data, 20 percent of Granite State students are still restricted to completely virtual learning.

Local school officials are unwilling to discuss the findings, but the research shows students pay a steep academic price when their classrooms remain closed.

An estimate from McKinsey and Company suggests that, if schools don’t return to in-person schooling until January 2021, students could lose between three and 11 months of learning. And, their study suggests, that price will be disproportionately paid by black, Hispanic, and low-income students.

And it appears that many of these children are being punished academically, not over public health but politics. A study by the Brookings Institute found a stronger correlation between school districts reopening and local support for President Trump than any metric in public health such as positive test rates.

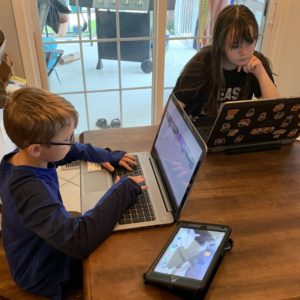

For the past seven months, New Hampshire students and parents have struggled with challenges of online and virtual learning and so far this year, nearly 20 percent of students have not returned to any in-classroom instruction while most schools have implemented a “hybrid model” where students will be in class throughout a portion of the week.

Governor Chris Sununu’s school reopening guidelines deferred all reopening decisions to local school boards. The result has been a clash between parents and teachers’ unions in cities like Nashua where in-person learning has been sidelined. In a recent press conference, Governor Sununu expressed optimism that the schools that are still doing remote learning exclusively may reconsider in the wake of the most recent data.

“The data shows there were about 60 or so kids out of 190,000 that currently are positive. That is a very, very low percentage. And hopefully they’ll use that data to make the decision to maybe advance into a hybrid model,” said Governor Sununu.

Between juggling schooling, work, and parenting, many New Hampshire parents are excited for the opportunity to get their students back into the classroom.

Mike Judge, a Mason parent of two, has a first-grader enrolled in Mason Elementary School. Mason Elementary is currently in a hybrid model where students attend in-person class for part of the week and complete the remainder of their learning online. Judge, a cybersecurity manager, sends his first grader to a neighbor’s house during the school day so he and his wife can focus on their work.

Judge acknowledged that his personal situation is better than many New Hampshire parents. He expressed concerns about the efficacy of online learning and noted that school attendance was low, possibly due in part to the lack of broadband in more rural parts of the state.

“Internet and working from home and learning from home has really put at the forefront the challenges that rural communities face,” said Judge. “There are days where our neighbor can’t get internet or kids that are learning can’t get internet. They don’t really do the course work. They’re not logging into the Zoom calls.”

Judge’s experience is common and according to a March survey of over 5,659 educators nationwide, 34 percent of teachers said that no more than one in four students were attending their remote classes. And according to the New York Times, as many as 25 percent of students in Los Angeles never logged in to online learning in the month of May. Lack of reliable and affordable internet access is widely considered to be one of the most critical factors in virtual learning success.

According to BroadBand Now Research, New Hampshire’s broadband access falls far behind Massachusetts but far outranks neighboring rural states like Maine and Vermont.

So far there have been very few cases in New Hampshire of students contracting COVID-19. The numbers from the University of New Hampshire show it’s far more likely that faculty and staff have contracted the virus than the students. And Pinkerton Academy recently had to switch to remote learning for a day, not because of students, but because of positive tests among teachers.

Thus far, not a single K-12 student has been hospitalized with the virus since schools reopened. It’s likely the vast majority of students who’ve tested positive were asymptomatic. The longer students remain out of in-person classes, the more likely it is that their learning loss will become exacerbated. Preliminary data projects an estimated 50 percent decrease in proficiency rates in third-grade reading and a projected 65 percent decrease in proficiency in math due to school closures.

Given the small, theoretical risk of COVID-19 and the demonstrable negative impact of remote learning, is it time for New Hampshire schools with closed classrooms to re-think their approach?