If you think the influence of the New Hampshire presidential primary has been exaggerated, just ask LBJ and George H. W. Bush—two incumbent presidents denied a second term in office by Granite State primary voters. (President Johnson dropped out in 1968. H.W. Bush should have after losing 40 percent of his party’s primary vote to fringe candidate Pat Buchanan.)

Before the GOP primary in 2008, John McCain’s presidential bid had been declared DOA. His New Hampshire primary win gave him front-runner status he never lost. The reason Hugh Jackman is starring as Sen. Gary Hart in a Hollywood movie today is because New Hampshire backed him over Vice President Walter Mondale in 1984, creating a serious White House contender…who would self-destruct three years later.

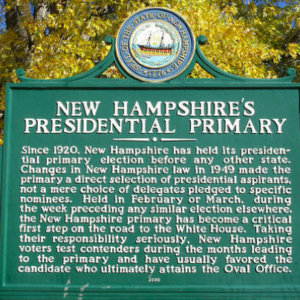

New Hampshire is where the make-or-break nomination process truly begins, but there are changes underway, both on the ground in New Hampshire and in national politics, that could mean an end to a tradition begun in 1920—and the beginning of a new order in American presidential politics.

A NEW SECRETARY OF STATE:

Since 1976, New Hampshire Secretary of State Bill Gardner has been the bulldog of the Granite State, defending the First in the Nation (#FITN) primary from challenges by other states, national party committees and top-tier candidates. And in every fight, Gardner came out on top—including 2008, when maneuvering by other states forced New Hampshire to hold their primary just three weeks after Christmas—January 8th.

For decades, Democrats and Republicans have given Gardner much of the credit for keeping New Hampshire at the front of the primary line, without regard for the fact that he’s a Democrat. In fact, Gardner is so apolitical that many Granite Staters are unaware of his party affiliation.

But just last week, New Hampshire Democrats in the legislature cast a non-binding vote to back Gardner’s opponent, Democrat Colin Van Ostern, for Secretary of State when the legislature convenes to elect the officeholder as they do every two years. The vote margin was a massive 179-23.

This will be Bill Gardner’s 22nd bid for a two-year term and he’s likely to lose it. Prominent politicians from both sides of the partisan aisle have stepped forward to promote Gardner’s re-election, but Democrats appear ready to make a change. Van Ostern, who ran for governor in 2016, is openly partisan and anti-Trump. While there are many partisan Secretaries of State across the U.S., the consensus from both sides of the aisle is that Gardner’s hyper-non-partisanship has helped New Hampshire defend its precarious first-in-line position.

New Hampshire Secretary of State Bill Gardner

What happens if Republicans conclude that New Hampshire is a partisan trap set in deep-blue New England? Or if Democrats decide they need to make a change for the good of the national party and move a more ethnically-diverse state to the front of the primary line? Will having a committed, anti-Trump Democrat overseeing the primary process make it harder to fight off threats?

A NEW FOCUS ON DIVERSITY

If you were looking for a state that reflects the Democratic coalition of 2020, you would be hard-pressed to find a worse choice than New Hampshire. West Virginia, maybe, but that’s about it.

“Get ready to hear a lot more about intersectionality, allyship, inclusivity and POC,” reports Politico in an article entitled “2020 Democrats Are Dramatically Changing the Way They Talk About Race.”

The impressive performance by progressive candidates of color in Georgia and Florida is sending the message that Democrats can win with the right mix of liberal ideology and identity politics. Both of which are in short supply in the Granite State.

New Hampshire is the third-whitest state in the nation (93 percent of the population is white non-Hispanic), trailing only Maine and Vermont. Less than 1.5 percent of the population is black. In a state of 1.3 million people, fewer than 20,000 are African-American. And only about 3.5 percent of the population is Hispanic.

Ideologically speaking, New Hampshire is hardly a harbinger of the modern Democratic coalition. The most senior Democrat in the state, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, is a moderate Democrat. Outspoken progressive Congresswoman Carol Shea-Porter was just replaced by moderate, pro-business Democrat Chris Pappas. Progressive activists in the state party’s primaries were wiped out by more moderate, mainstream candidates.

And Democrats are noticing. Progressives, who are already frustrated by the fact that former Vice President Joe Biden tops the current polls of 2020 primary contenders aren’t happy about starting the primary process in a place where so many of the voters are in Biden’s demographic.

As a result, many of the 2020 candidates are already focusing on South Carolina’s “first in the South” primary and its far more racially-diverse population.

“I think how politics is done in South Carolina is a true reflection of where we need to be as a country,” Democratic strategist Antjuan Seawright told CNN this summer. “So goes the south, so goes the heartbeat of America.”

There’s a similar dynamic for the GOP, but from an ideological standpoint. Beginning in 2019, Democrats will control the entire federal delegation and both chambers of the state legislature. The only Republican still standing is Chris Sununu, a pro-choice, pro-same-sex-marriage moderate who will never be confused with a classic GOP primary voter.

And while President Trump has the backing of most Granite State Republicans, his level of support is about 10 points lower than among the GOP nationwide. It’s a state where John McCain Republicanism is still relatively popular, which makes it an outlier for the party as a whole.

New Hampshire Republicans argue this is a good thing because it pushes their party’s nominee toward the center. Conservatives argue that the Granite State is an electoral aberration and the real primary starts once the race heads south.

As a result, both Democrats and Republicans have reasons to re-think their commitment to New Hampshire’s #FITN status.

THE PARTY OF TRUMP

One of the many victims of the #BlueWave that crashed over New Hampshire politics in the midterms was the state’s Republican Party itself. The New Hampshire GOP is a largely volunteer organization and it was both outworked and outspent by its full-time, well-funded Democratic counterpart.

As a result, its performance in the November elections has been widely panned and there’s a leadership battle brewing for control of the state party apparatus. And the name at the center of that battle? Donald Trump.

A former state representative and co-chair of Trump’s New Hampshire campaign, Steve Stepanek, has announced he’s running for state party chair.

“At this juncture, the Republican Party doesn’t exist in New Hampshire as far as an organization,” Stepanek said in his announcement.

While most Republicans agree with his assessment of the problem, they have concerns about Stepanek, a Trump loyalist, as the solution. The less-Trump-friendly locals are concerned that he might abandon the tradition of maintaining a level playing field for potential primary candidates.

“In order to protect the New Hampshire first-in-the-nation primary, I am required and will be completely neutral if there is a primary challenge to the president because that’s the job,” Stepanek insists. However, President Trump has an outsized focus on loyalty, and many Republicans are concerned that a Trump-friendly state party chair could be pressed into service on behalf of the incumbent, thus undermining the credibility—and value—of the New Hampshire Republican primary.

If Republicans nationwide believe that New Hampshire is no longer a neutral playing field, their support for its First in the Nation status may fade.

History shows that the Granite State’s #FITN tradition is always in danger. The 2020 calendar appears to be set (Iowa on February 3, New Hampshire eight days later), but anything can happen in the next 12 months, and even if 2020 goes smoothly there’s another fight on the horizon for 2024.

Individually, these issues can be managed by New Hampshire and its other early-state allies. But put them all together and suddenly the Granite State’s place in American politics no longer looks like its set in stone.