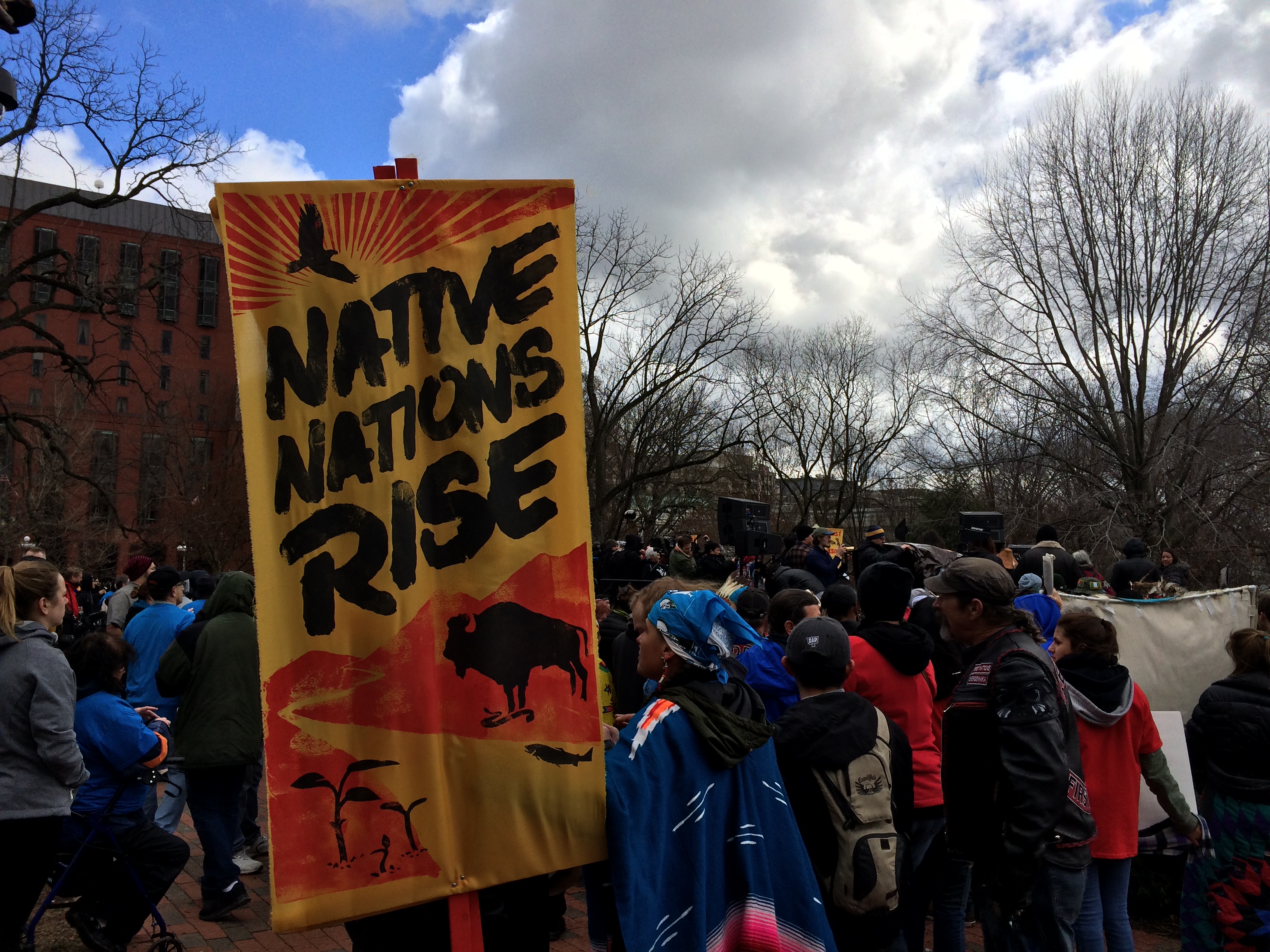

Dakota Access Pipeline protesters continued their opposition to the project Friday by taking their fight to Washington, D.C.

The North Dakota-based protests began early last year in response to the pipeline being approved. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and environmental groups warned the project posed a threat to the local population. The resulting protests lasted for months and included thousands of participants.

The Standing Rock tribe has been at the forefront of the protests. The tribe has argued the pipeline threatens their drinking water and land. It also claims the pipeline threatens sacred grounds. In truth, the pipeline never crosses onto tribal land. The tribe rebuffed attempts by the Army Corps of Engineers to meet and discuss the route.

“You can’t drink oil,” protester Lara Calloway told InsideSources. “This isn’t just a native issue. It’s an issue for all future generations, although they were here first. We’re just standing in solidarity, not only with the Standing Rock Sioux but also the other native nations.”

The North Dakota protests lasted into the winter with many setting up shelters for the cold. The weather eventually grew too cold for most of the protesters, but a small group remained. Law enforcement was able to clear the remaining protesters and campsites in February.

“We got evicted from out there and put out of our teepees and our homes there,” protester Nathan Phillips told InsideSources. “So here we are with the support of others expressing our need to continue with this struggle to protect the water so that’s what we’re doing here because what happened out at Sacred Stone and Standing Rock was just the beginning.”

Phillips lives near the pipeline location and is a member of the Omaha Tribe. He clarified that he wasn’t evicted from his house when asked by InsideSources. The protesters were eventually compelled to leave the campsites that were setup for the protests.

“Yeah, I was out there in my teepee, staying out there,” Phillips said. “I’ve been out there since Thanksgiving. So according to rules and laws, I guess I was a resident out there and it was my home. They came out and forced me out.”

The camps were, in fact, on Army Corps of Engineers land, where protesters were causing environmental damage, and there was danger from spring flood waters.

Environmentalists argue that pipelines pose a huge threat to the regions they’re built through. The pipeline could pollute the environment by leaking or spilling. Many protesters were opposed to the pipeline outright, beyond just the tribal concerns.

“Pipelines are very dangerous, they’re horrible for our planet,” protester Ezekiel Baegage told InsideSources. “They leak into the soil, and they leak into the water. But it’s not just the pipeline. They’re violating the civil rights, and they’re breaking treaties. These oaths that they signed.”

The Dakota Access route runs parallel to an existing pipeline, and eight other pipelines cross upstream from the reservation.

The Fraser Institute, a conservative research group, found the concerns are typically overblown. It detailed in a report that pipelines are actually a safer method for transporting oil. The report notes pipelines are 4.5 times safer than railways that are transporting over the same distance.

“I think perhaps, maybe it is, but the fact is, it’s not a matter of if the pipeline bursts, it’s a matter of when,” Calloway said. “Maybe it is safer than certain railways and stuff. But I think a lot of people who are here are trying to get people invested in renewable energy.”

Calloway adds it doesn’t matter if it’s safer because the risks are too high. She notes more needs to be done to advance renewable energy. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers suspended the project last year to conduct an environmental assessment in response to political pressure from within the Obama administration, despite the belief by the corps that the pipeline would improve safety.

“I was at Standing Rock for a little over a month,” Baegage said. “What brought me out there was the people. I wanted to protect the people, I wanted to protect the land. When I saw what was going on, I didn’t want them to be hurt, I didn’t want anyone to be hurt.”

President Donald Trump restarted the pipeline construction soon after taking office. He signed a presidential memorandum to advance pipeline construction. The move expedited a secondary environmental review process ordered by the Corps of Engineers last winter and ended the public comment period.

“A lot of people don’t know about us, and coming out here I see that even more,” Baegage said. “I wanted to come out here to show that we are still here. We’re still resisting, we’re never going to leave and just because that one fight has stopped, doesn’t mean the other ones will.”

The Army Corps of Engineers was denounced by protesters for not meeting with tribal leaders. The Standing Rock tribe, however, cancelled meetings and declined to offer comment at the request of the corps. The tribe was alerted to the pipeline permit application in the fall of 2014. The corps held 389 meetings with 55 tribes over that time.

Energy Transfer Partners, the company building the pipeline, also held numerous meetings. It worked with federal, state, and local officials to find the safest and most effective route. Project leaders participated in 559 meetings to listen to officials and other interested parties.

The Dakota Access Pipeline starts at the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota. The pipeline will then run through South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois. It will eventually connect with a preexisting pipeline which will transfer the crude oil to refineries on the Gulf Coast.

![Facts Missing as DAPL Protesters March on D.C. [PICTURES]](https://insidesources.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/IMG_8755-300x300.jpg)